What Is the Capital Stack in Multifamily Real Estate?

The first time I heard somebody use the term “capital stack,” all I could think of was a big pile of cash. I was pretty sure “first position” had something to do with dance—and when I heard someone reference “mezzanine debt,” I thought it was somehow related to stadium seating options. Maybe “mezzanine debt” was a season-ticket financing plan?

Eventually, I educated myself on such things, but I probably should have made an effort to know the lingo a little sooner.

As you start to do bigger multifamily deals, it’s helpful to understand how larger investors look at projects and get a better grasp of the terminology, some of which isn’t widely used for smaller properties. An important part of that perspective is understanding deal structure, which is often no more complicated than for a duplex, but on occasion, it can get much more so.

Key takeaways

- The two types of capital used to fund a deal are debt and equity, both of which can come from different sources. They are layered on top of one another to make up the capital stack. Where each source falls relative to the others in the capital stack reflects repayment order if the project fails.

- Debt is the cornerstone of most deals and is usually in the first position at the bottom of the capital stack. Equity/cash is at the top and is last in line for repayment.

- The most common ways to come up with equity are contributing the cash yourself or forming a joint venture or a syndication. Each option has its own advantages and disadvantages.

What types of capital can fund a deal?

Two types of capital are used to fund a deal at a high level: debt and equity. The capital can come from different sources, and the sources are layered on top of one another to cover the project’s cost. Combined, these layers make up what is referred to as the capital stack.

The capital stack reflects the sources and where each source falls relative to the others in terms of first rights of repayment should the property not perform.

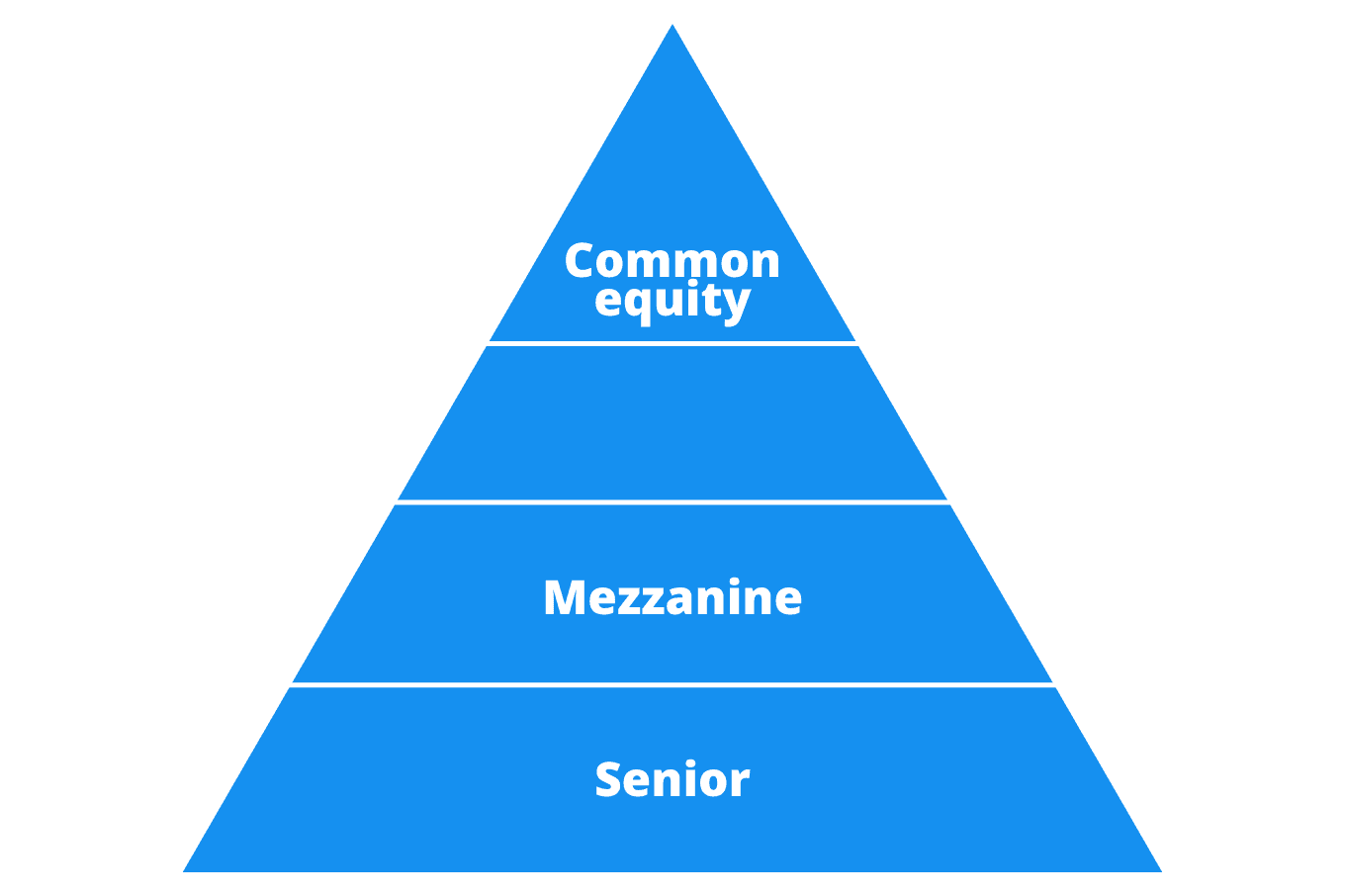

Capital stacks are often depicted graphically in the shape of a pyramid. At the bottom are the people or entities who would get paid first if everything falls apart, which means this is the place on the pyramid where capital is the least at risk. In most deals, the lenders are at the bottom of the capital stack.

The equity you contribute out of pocket is almost always going to be at the top of the pyramid. You will not get paid until the debt obligations are fulfilled, so your funds are at the greatest risk. But you also have the greatest exposure to the upside.

In general, the risk declines as you go lower in the capital stack, but so do the returns.

Using debt as a funding source

Debt is the cornerstone of most deals. In most large multifamily transactions, debt covers 65% to 80% of the purchase price. That said, Brandon and I have both done all-cash deals for which we didn’t borrow any funds, as well as deals for which we’ve financed 100% of the purchase price.

Many investors with limited cash resources dream of purchasing a multifamily property with all debt and no equity. While buying a multifamily property with no cash out of pocket is possible, finding these opportunities is exceptionally challenging. Over the past decade, I have been involved in hundreds of deals, but I’ve funded only two properties with 100% debt, and both were facilitated through strong lender relationships.

The reality is that you’ll need at least some cash to close most deals, although it doesn’t necessarily have to be your own cash.

While closing without much cash or even walking out of closing with a check in your pocket might seem exciting, you should be cautious about structuring deals this way. Just because you come across a situation that allows you to put in less cash doesn’t mean it’s the right thing to do. Taking on debt involves risk, so you must be careful not to overextend yourself.

Both Brandon and I have employed creative financing techniques when we knew properties would generate more than enough cash flow to cover our debt service safely. On other occasions, we have each walked away from opportunities to use high leverage because we weren’t able to identify enough opportunities to add value or didn’t want to take on the higher risk associated with the debt.

Grow your portfolio with multifamily

Multifamily real estate investing can turn anyone into a multimillionaire—but only if you run your business the right way! In this two-volume set, The Multifamily Millionaire, authors Brandon Turner and Brian Murray share the exact blueprint you need to get started with multifamily real estate.

Structuring a deal with debt

How much debt you can secure typically depends on the specifics of the property and the deal you negotiate. The amount of debt most lenders are willing to extend is in large part dependent on how much cash a property is generating and its ability to cover the mortgage payments.

In terms of the capital stack, the largest debt is most commonly found at the bottom of the stack in the first position, which is secured by the property. The debt in the first position is also called the senior debt. What is the significance of being in the first position? Basically, if you were to default on this loan, this note holder can foreclose and would be paid before anyone else in the capital stack.

Sometimes there will be a lender in a second position that extends mezzanine debt, subordinate to the senior debt. This second position in the capital stack fills the gap between senior debt and equity.

For our River Apartments project, for example, the mezzanine debt was extended by the seller. Another example of mezzanine debt is when developers get landowners to partner with them or finance the land portion of the deal through construction.

If there is ever a foreclosure sale, the lender in the second position will get paid only if proceeds were left over after the first lender was made whole. Banks are not generally comfortable with the risk of being in the second position, so this debt is more likely to be secured from the seller or a private lender. There are some lenders out there, usually debt funds, who do only mezzanine debt and charge a higher interest rate to offset the higher risk.

Below is an example of a potential capital stack.

Equity

Equity is the cash portion that sits at the top of the capital stack. In most situations, you will either put this cash in yourself or secure it from partners or investors. For development projects and major restorations, however, equity will often come from various creative sources such as federal and state historic preservation tax credit programs, low-income housing tax credits, state and local development grants, and in some limited cases, even the EB-5 Immigrant Investor Program.

A savvy entrepreneur with expertise in these programs can sometimes put a development deal together with very little of their own cash, though the devil is in the details. Most of these programs can get complicated and involve long and arduous slogs through bureaucracy, politics, and paperwork. In many cases, you may find yourself looking at multiple years of development efforts before a project will actually cash flow. Most grant programs require you to front the cash and apply for reimbursement after the work is complete.

For more traditional multifamily acquisitions, the three most common ways to cover the equity portion are to contribute all the cash yourself, do a joint venture with other investors, or syndicate the deal. Each of these options comes with its own advantages and disadvantages.

More on multifamily from BiggerPockets

Going solo

The first option is to cover all the cash requirements of a deal by using your own capital. The legal entity of choice for going solo on a multifamily deal is the single-member limited liability company (SMLLC).

The biggest advantage to funding a deal yourself is that you can have 100% ownership and control of the property. The downside is that you have to come up with the funds. They might come from your personal savings, the sale of other investments, a line of credit, or anywhere else you can drum up some cash.

For my first deal, I drained my retirement account, which I don’t recommend. After that, I tried to avoid using my meager personal savings. For most of my deals, I could secure the necessary cash from adding value to properties in my portfolio and doing cash-out refinances.

Using this approach, I accumulated a portfolio of more than 500 units, plus a handful of office and retail properties. I did a couple of joint ventures along the way, pooling my resources with partners. Later, after more than a decade of going it alone, growing organically, and being perpetually cash-poor from reinvesting all my profits into more deals, I decided to partner and start syndicating. This allowed me to take my portfolio to the next level, accumulating units in the thousands.

Joint venture

A joint venture basically entails teaming up with other active investors to do a deal together. The most common way to structure a real estate joint venture is by forming a multi-member LLC, but there are many other potential legal entities you could use. The advantages of a joint venture include the ability to leverage the skill sets and connections of multiple people and the ability to share the workload. Perhaps more importantly, you can pool resources and acquire larger properties than you could manage by yourself.

The downside of joint ventures is that you’re taking on all the potential perils and pitfalls of investing with partners. You won’t keep all the equity either, and depending on how the operating agreement is written, you may not have full control. That said, you are getting a smaller ownership stake in what is likely to be a much larger deal, so you could consider it a wash from an equity standpoint.

A joint venture requires a lot of up-front communication to make sure everyone is on the same page. Responsibilities and ownership should be defined in the operating agreement and can be divided in any way agreeable to the parties involved.

How much each partner contributes toward the cash required for closing is also flexible. Cash contributions can be split equally among the partners. They can be divided to reflect each partner’s relative amount of responsibility for, say, the acquisition or day-to-day operations. It’s not uncommon, especially in smaller multifamily properties, for one party to put in all the cash and one to put in most of the work, or “sweat equity.”

That said, all partners in a joint venture must have some active role in the investment, even if it’s minor. If any of the owners are 100% passive, the investment could technically be considered a security and subject to securities law. If you want to accept money from 100% passive investors, the deal should be structured as a syndication.

Syndication

A syndication is a limited partnership that involves the pooling of money from passive investors to fund a deal. In return for contributing cash, these passive investors, who are limited partners, get part ownership and a preferred share in the profits.

By preferred, we mean that the people who invest in your syndication would be the first ones to receive a defined portion of the returns after debt obligations are met. This means you will have two types of equity—common and preferred.

As shown in the earlier illustration of a sample capital stack, preferred equity sits above debt but below common equity. As the one who pulls the deal together, you would be a general partner and hold common equity (sometimes called sponsor equity), which sits at the top of the capital stack and is subordinate to all other debt and equity holders. As a general partner and common equity holder, you are paid last.

On the downside, syndications are significantly more complicated than joint ventures from a legal standpoint, and they usually involve giving up a lot of equity. Depending on how much of the capital you are raising from the limited partners, your ownership stake can end up being severely diluted compared to going solo.

That said, giving up a hefty chunk of equity to passive investors can be fulfilling because it provides you with the opportunity to create wealth for others. However, the real beauty of syndicating a deal is that it allows you to buy properties far larger than you would otherwise be able to afford.

Some syndicators contribute cash alongside passive investors, but many syndicators raise all the necessary capital from others. That’s the big attraction of syndication for many investors: You can buy large multifamily properties with no cash!

Syndication has become popular because it enables investors to successfully scale to large levels relatively quickly. We’ve met syndicators who have amassed thousands of units in just a few short years by raising capital to fund their deals. In fact, the fund we own grew from zero to more than 1,000 units in 18 months, thanks to syndication. It’s a great strategy but also a complex one.

This blog post is an excerpt from Chapter 2 of The Multifamily Millionaire, Vol. II by Brian Murray and Brandon Turner. If you’d like to learn more about finding the right deals, achieving the right cash flow, and running your multifamily business the right way, buy the book today!

:215-447-7209

:215-447-7209 : deals(at)frankbuysphilly.com

: deals(at)frankbuysphilly.com